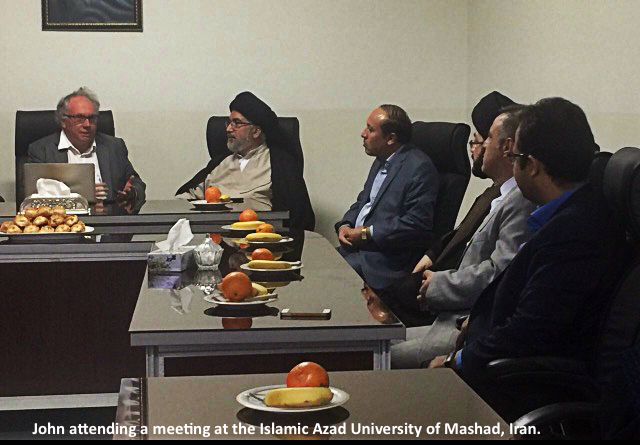

For 24 days in May I enjoyed wonderful hospitality in Iran as a guest of Dr Mohammad Farajiha of Tarbiat Modares University. With his inspiring group of graduate students, Dr Farajiha organized a culminating conference in Tehran on Restorative Justice in Iran*, which was attended by visiting scholars from Iraq, the UK, the US, France, Belgium and Canada.

*(the conference website is in Persian, but you can use google to translate it into your preferred language)

A remarkable 320 Abstracts were submitted to the conference by Iranian scholars. Only 42 could be selected for presentation. Hence, one of my jobs was to travel to all corners of Iran giving 9 presentations at workshops with participants who could not get into the Tehran conference. Large university lecture theatres were mostly overflowing at these events.

It is a time of hope in Iran in a number of ways. While President Obama’s administration has been a disappointment in some ways, Iran is a case like Cuba and Myanmar where his principled engagement with previously demonized regimes has paid handsome rewards. This could make the world a safer place for decades to come.

The Iran nuclear deal has helped a wider thaw and is a masterpiece of the regulatory craft with its trust-building and ‘snap-back’ sanctions design. It has enormous grass-roots support among the people of Iran—partly because it is a fresh start to principled engagement.

The most striking thing about restorative justice in Iran compared to the West is the importance of the principle of forgiveness. Many common kinds of criminality are formally classified as ‘forgivable’ crimes in Iranian criminal law. Most murders are formally forgiven by victim families in Iran, and in many cases the forgiveness is heartfelt. When victims choose to forgive, prosecutors are mandated to defer to the victim’s right to forgive. Rape is one of the important exceptions; it is a crime against God in Iran’s Sharia tradition.

Another major category of exception is economic crimes—like environmental crime, tax fraud, securities or insurance fraud or forgery—that are seen as crimes against society rather than against an individual victim who has a legal right to forgive that crime.

Even so, Iran is the site of interesting innovation with restorative justice for corporate crimes including industrial safety and environmental offences and fraud by insurance companies. I am hoping to study this innovation further on another visit to Iran in 2017.

I had meetings with three Grand Ayatollahs in Qom and Tehran, including a retired former head of the Iranian judiciary. All three Grand Ayatollahs emphatically endorsed the view that restorative justice is strongly an implication of the principles and the jurisprudence laid down in the Holy Quran.

Inter-university scholarly engagement is an important way of contributing to peacebuilding with formerly demonized regimes, especially when the topic of engagement is mutual learning about how to advance peace with justice through restorative principles.

Thank you very much Prof. Braithwaite for this insightful posting on your encouraging scientific journey to Iran. The potential for an authentic Iranian contribution to RJ scholarships and practices are there, as you rightly mentioned in your brief report here. Let me only add that the RJ thinking can be greatly benefited from the key Persian cultural and spiritual heritage i.e. the works of Rumi. Rumi’s spiritual works, all in Persian originally, do directly influence various aspects of lives of millions of Iranians, Afghans, Tajiks, Kurds and even Turks around the world. Rumi’s Masnawi, major Sufi work of the world, is called the Persian Holy Quran.

Wish you all the bests for the future journeys to Iran, the ancient land of culture.