Responsive regulation is about ‘tripartism’ in regulation. It highlights the limits of regulation as a transaction between the state and business. It argues that unless there is some third party (or a number of them) in the regulatory game, regulation will be captured and corrupted by money power.

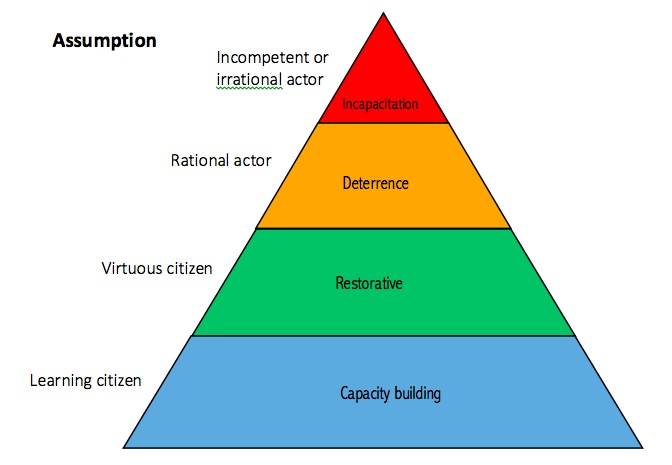

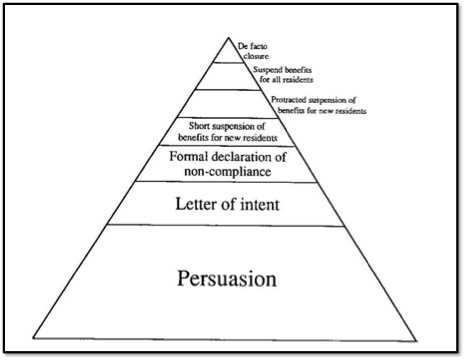

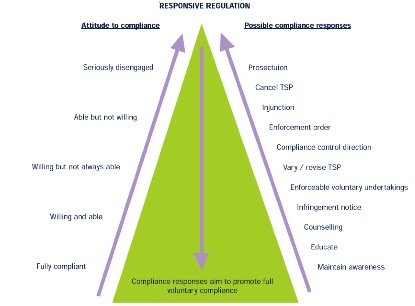

Responsive regulation involves listening to multiple stakeholders and making a deliberative and flexible (responsive) choice from regulatory strategies that can be conceptually arranged in a pyramid. At the bottom of the pyramid are more frequently used strategies of first choice that are less coercive, less interventionist, and cheaper.

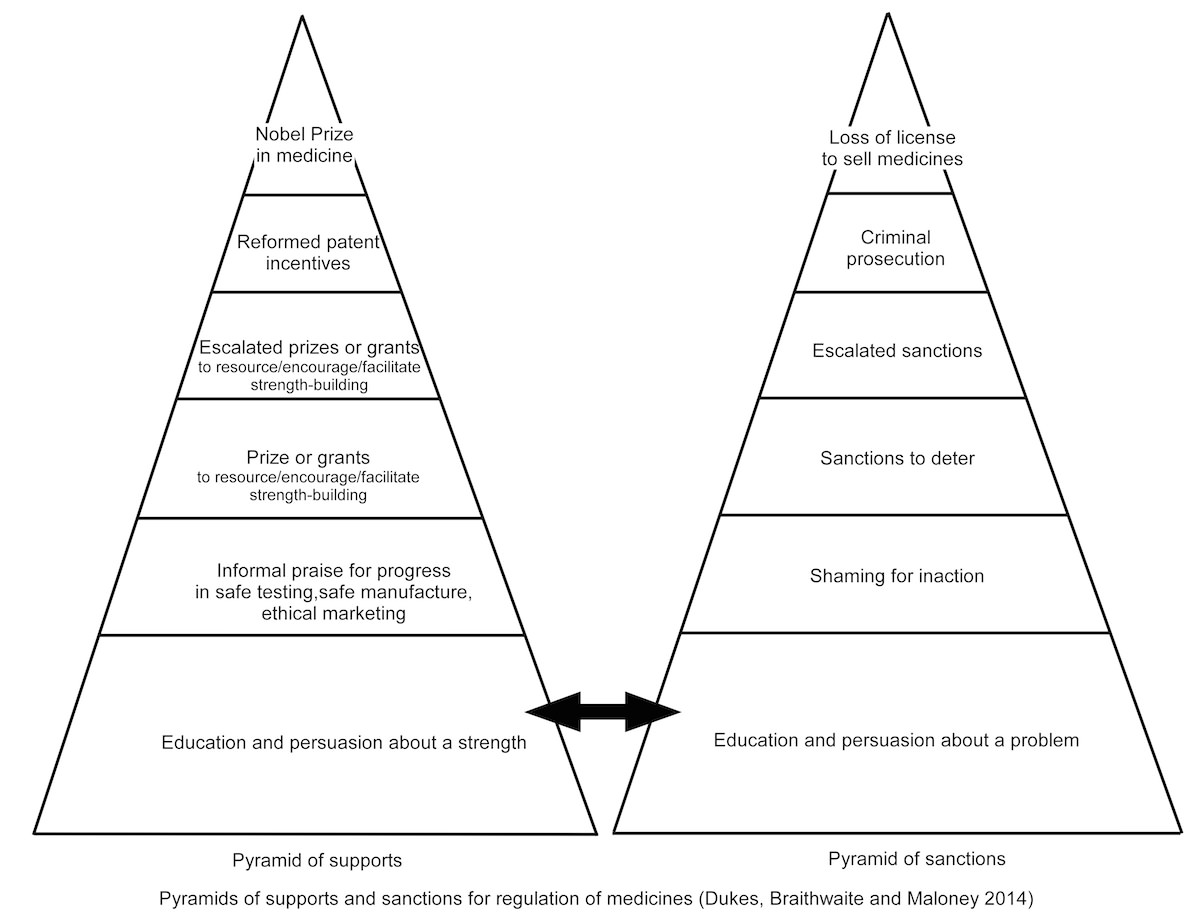

Below are some examples of responsive regulatory pyramids. There is a presumption for trying the strategies lower in the pyramid until they fail. Then the weaknesses of these strategies might be covered by the strengths of strategies higher up the pyramid. Signaling to stakeholders the capacity to escalate to ‘the tough stuff’ higher up the pyramid motivates cooperative problem solving at the base of the pyramid:

The essence of responsive regulation describes why the flexible listening components of responsive regulation are more fundamental than the pyramid.

Over time we realised it was important not only to pick problems and fix them but also to pick strengths and expand them. For example, industry leaders take self-regulation up through new ceilings and then drag laggards up toward their standards. So we complemented the pyramid of sanctions with pyramids of supports. This example is for pharmaceuticals regulation:

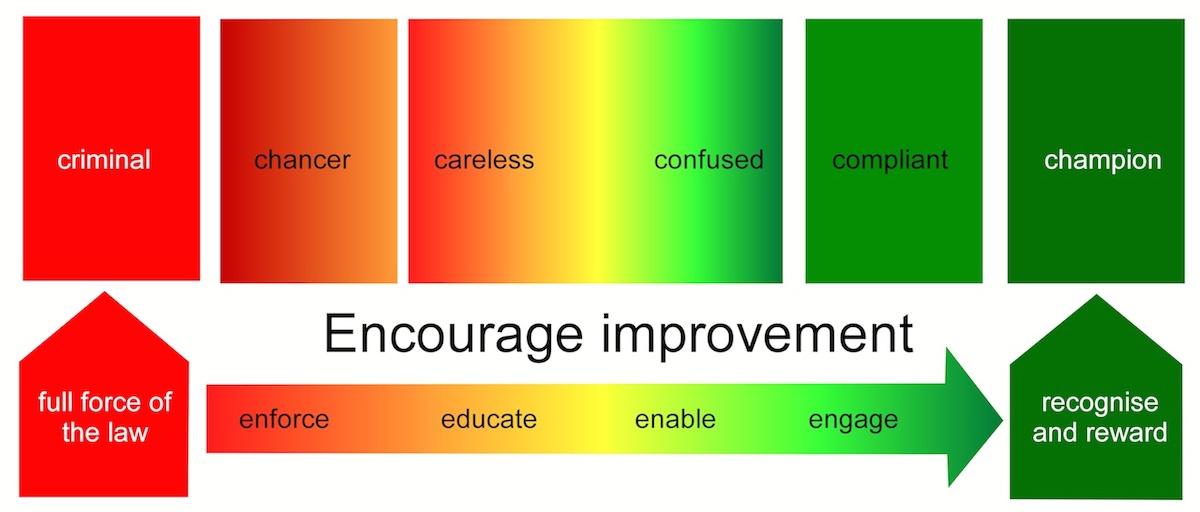

The South Australian Environmental Protection Agency has simplified this idea elegantly for its regulatory strategy:

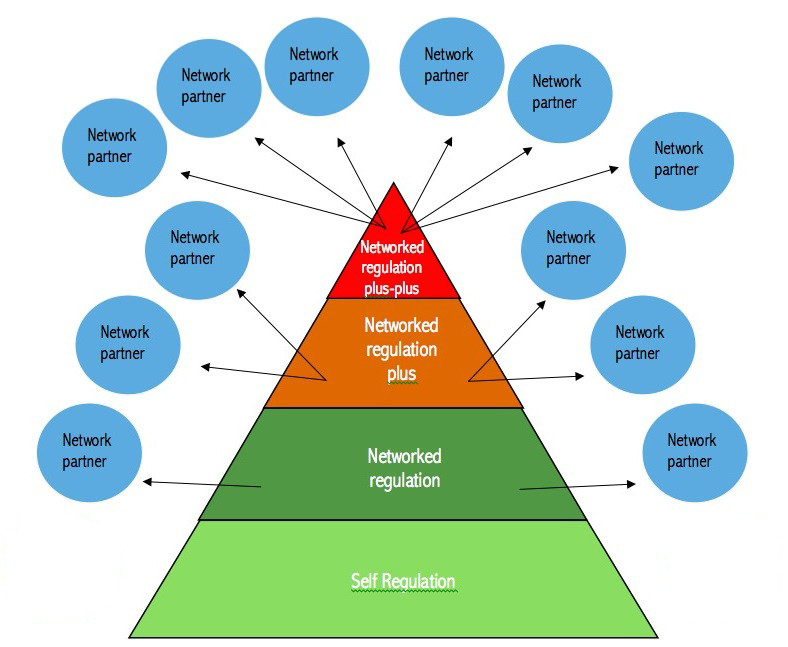

Because poor countries struggle to escalate state regulation against powerful corporations, the next move was then to a pyramid of networked escalation. Peter Drahos’s influence on the development of this pyramid is discussed in J. Braithwaite (2006) “Responsive Regulation and Developing Economies“.

Recent publications provide evidence that responsive regulation is effective and include:

- Schell-Busey, Natalie, Sally S. Simpson, Melissa Rorie, and Mariel Alper. 2016. ‘What works? A systematic review of corporate crime deterrence’. Criminology & Public Policy 15(2) (available here).

- John Braithwaite, 2016. In Search of Donald Campbell: Mix and Multimethods. Criminology & Public Policy 15(2) (available here).

- Ka Wai Choi, Xiaomeng Chen, Sue Wright and Hai Wu. 2016. Responsive Enforcement Strategy and Corporate Compliance with Disclosure Regulations (available at SSRN)

- Restorative and Responsive Regulation: The Question of Evidence. RegNet Working Paper No. 51, School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet) (free pdf)

- Mary Ivec and Valerie Braithwaite with Charlotte Wood and Jenny Job. 2015. Applications of Responsive Regulatory Theory in Australia and Overseas: Update. RegNet Occasional Paper 23, School of Regulation and Global Governance.

- And more than 100 working papers, many based on qualitative evaluations, on Valerie Braithwaite’s Centre for Tax System Integrity website.

- Video: Radical Ideas in Justice and Regulation, J. Braithwaite, Ronin Films, 2014.

You can also watch a video explaining some of the key ideas in responsive regulation, below.

KEY PUBLICATIONS ON RESPONSIVE REGULATION

The following publications developed the ideas of responsive regulation in the early years. Only after Ian Ayres joined us was ‘responsive regulation’ used to describe this work.

The following books are extended applications and refinements of responsive regulation: