Around the turn of the century, the Australian Tax Office took some rather effective responsive regulatory initiatives to counter profit shifting by multinational corporations. The measures involved negotiating with major accounting firms and targeted companies who were paying little or no tax to display to them a regulatory pyramid of escalated monitoring and sanctions unless their profit shifting became less aggressive. This responsive regulatory program raised an extra billion dollars in tax for every million dollars spent on it. That research is reported in my 2005 book Markets in Vice, Markets in Virtue and in my 2003 article ‘Meta Risk Management and Responsive Regulation of Tax System Integrity’.

In the past decade, profit shifting by multinationals and the use of tax havens by rich individuals has become even more aggressive than it was at the turn of the century, more difficult to manage. Even so, my basic advocacy remains that while national and international tax law reform is important (see Markets in Vice, Markets in Virtue), tax enforcement reform is much more important than tax law reform.

It has been quite unacceptable for our tax authority in Australia to accept a situation for 12 years in a row since the time of that program where Starbucks paid no company tax, for example. Long before today, our tax Commissioner and Treasurer should have been pushing that tax return back across the table to the Starbucks CEO with the stern riposte: “I suggest you reconsider and resubmit your tax return before proposing to us another year where you make no contribution to the roads, the policing and health services that benefit your company and its employees.”

We all know that is what the Chinese government would do. China does not play the game purely at the level of clever tax lawyering because they know that is to play it on the corporate tax lawyers’ home ground. Those corporate lawyers will have some clever argument about how the brilliant Starbucks business model is why their coffee is best and this involves a patent that demands payment of those profits to some low tax jurisdiction where that patent is owned. Or some other argument of that kind. Let’s assume that Starbucks’ argument is right at a tax technical level. What we want is an aggressive tax authority that is clear that it will take that kind of argument to our courts with the submission that Australia’s General Anti-Avoidance law should be interpreted to cover that situation and to require Starbucks to pay tax.

If the courts do not interpret our General Anti-Avoidance law sufficiently widely to make Starbucks pay a similar amount of tax to the mum and dad coffee shops who compete with them, let us have that failure of our legal system exposed in the courts to the people of Australia. Let us then have clamour for the needed reforms, including a more expansive general anti-avoidance principle in our law, as argued in Markets in Vice, Markets in Virtue.

My argument is that a tax commissioner and a Treasurer who had been appropriately aggressive in executing that strategy would have persuaded Starbucks not to face the costs of fighting this in the courts. In the meeting described above, where the tax return was pushed back across the table, the Tax Commissioner would have persuaded Starbucks to take their tax return back and re-submit it with a credible tax payment. Tax officials say to me, ‘yes China can do that but we in Australia do not have the clout to play the enforcement game in that way’.

I do not believe this.

If Australia’s Treasurer had been clear enough about taking an aggressive stance toward highly profitable companies not paying tax, Starbucks would have backed off a decade ago, even if they believed their tax position was right and believed they would have won in the courts. They would have willingly paid much more tax than what they would have had to pay to their high priced lawyers to fight the Australian government in such a court case. The reason for this is less the legal costs of the fight or the risk they might lose in the courts, but the reputational risks from winning such a case. They would have settled a handsome payment to the Australian Treasury because of the press release such an aggressive Treasurer would have put out after his tax office lost the case.

image from coffee uncut

It is not the case that only China has the clout to play the game this way. For a couple of decades, the little Netherlands has had a tax authority with a responsive regulatory strategy of this kind. Wall Street tax lawyers hated them for it as I reported as long ago as the publication of Markets in Vice, Markets in Virtue.

Critics of responsive regulation always saw tax enforcement as a least likely domain of regulation for responsive regulation to work. One reason was that critics said responsive regulation relies on repeated encounters with regulatees; and tax authorities rarely have repeat encounters with taxpayers. This was a mistaken critique first because all responsive regulators can concentrate their repeat encounters on targets suitable for sending strategic messages to the entire society through press releases. Second, tax authorities do have repeated encounters with tax accounting firms that are the key mediators of these enforcement messages to their clients. Third, these critics ignore recent theoretical and empirical development of the implications of indirect reciprocity for the efficacy of responsive regulation. This research is being led by Seung-Hun Hong[1].

Another reason critics of responsive regulation were concerned that responsive regulation could not work with tax enforcement was that there was no third party with tax enforcement in the way the environmental movement is a third party with strategic environmental regulation, or the trade union movement with occupational health and safety enforcement. This latter critique was the one that worried me most.

In Australia, the welfare lobby, particularly the Australian Council of Social Services, has long played a minor role. When I represented consumer and community groups on the Economic Planning Advisory Council in the 1980s I played a very minor role. It would embarrass the Tax Commissioner and the Treasury Secretary when I attacked our limp tax enforcement posture in front of the Prime Minister, the Treasurer, other Ministers and state premier—especially when trade union leaders joined in with the criticism. But this was just a monthly one-day meeting where tax was often off the agenda, so it was weakly episodic pressure, as were my infrequent visits to the ATO.

Today, international pressure has changed the third party landscape for the good. Oxfam is one organization that has done a wonderful job of exposing companies and wealthy individuals who are not paying their fair share of tax internationally and in Australia[2]. With an operating budget of less than $1 million, the Tax Justice Network has been the biggest change agent. Its scrutiny is mobilized by volunteer tax activists and researchers, including some who were part of Valerie Braithwaite’s Centre for Tax System Integrity. Thirdly, the Panama Papers whistleblower made a major third party contribution.

All this is strengthening the hand of tax officials who want to play a responsive regulatory hand aggressively. It is also putting national courts under pressure to adopt a more purposive approach to interpreting tax law in accord with the principles that underpin tax law. And it is building pressure for more expansive interpretations of general anti-avoidance principles. Perhaps this new international tax activism will succeed in changing tax laws for the good. Maybe it will fail to reform the law. But even if it does fail, the third party pressure I have just described is already changing the behavior of tax officials, courts and political leaders. Australian Labor Senator Sam Dastyari deserves an honourable mention here.

More importantly, all this is directly impacting the ethical climate in major accounting firms, multinational corporations who have paid little tax in the past, and even the ethics of rock stars and sporting icons who now worry about being exposed for paying no income tax. On a variety of fronts these developments have improved voluntary taxpaying by the likes of Starbucks in many countries. Of course there are also worries about how the increased exposure to adverse publicity of wealthy actors will affect voluntary cooperation with providing information to tax authorities.

Tax authorities are also increasingly adopting the advice of Markets in Vice, Markets in Virtue to turn up the tenacity of tax enforcement by relying more heavily on bounty payments to whistleblowers. The US Internal Revenue Service paid former UBS banker Bradley Birkenfeld $104m for spilling the beans on the Swiss bank’s ingenuity with offshore accounts. Birkenfeld approached the Department of Justice offering to lift the covers on all manner of UBS intrigue. This even ran to bankers using toothpaste tubes to smuggle diamonds across borders for clients. The IRS seized an opportunity—what I would call a responsive regulatory coup—with the bank, avoiding criminal prosecution by agreeing to pay a $780m fine and suffering a windstorm of adverse publicity that must have its clients pondering the safety of their secrets with UBS. And indeed with other Swiss banks. Of course, the windfall for the revenue was not mainly the $780 million fine, but the clients of UBS and other Swiss banks who decided to come clean and make their tax obligations transparent.

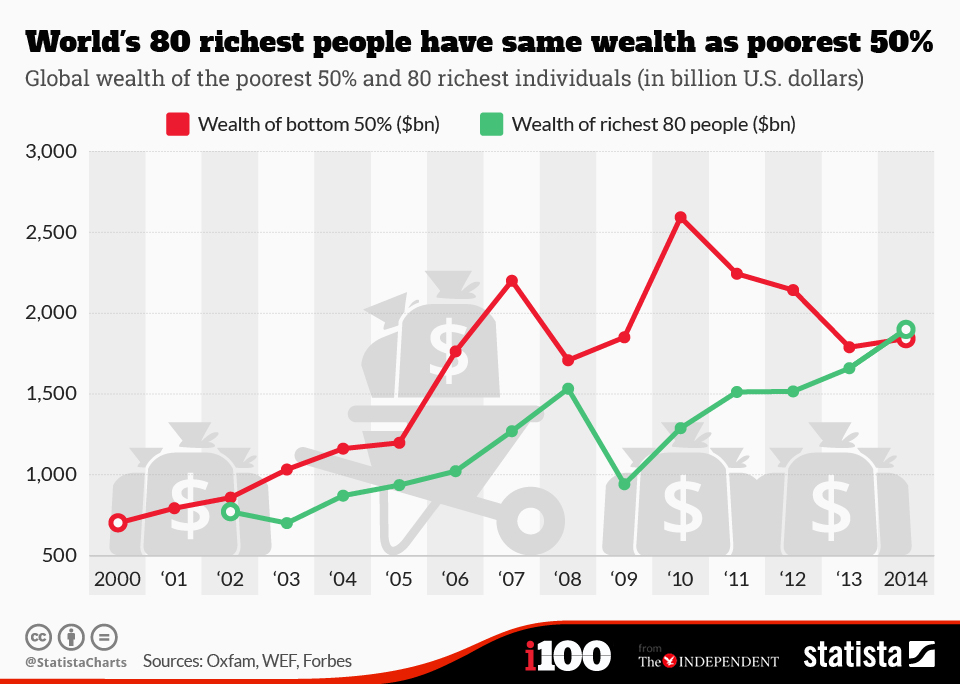

None of this transforms in any dramatic way the disastrous contribution that tax policy has been making in recent decades to widening global inequality. Yet it helps in a non-trivial way to shift the game in the direction of justice and decency.

[1] see J. Braithwaite and S. Hong (2015) ‘The Iteration Deficit in Responsive Regulation: Are Regulatory Ambassadors an Answer?’ Regulation and Governance 9(1), 16-29.

[2] see Oxfam’s ‘The Hidden Billions: How tax havens impact lives at home and abroad.

Leave A Comment